|

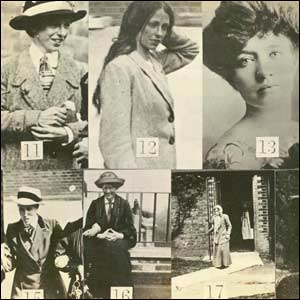

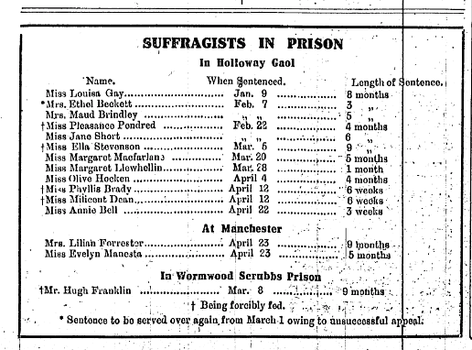

Seen the Suffragette film and interested in finding out a bit more about the stories it tells? Well, hello! 1. Police Surveillance PhotosIn the Suffragette film, we see police taking and collating surveillance pictures of suspected militant women both out in public and whilst they are in prison. As violent direct action became more frequent, surveillance of militant women and their networks by police increased. The photographs could then be circulated not only to police forces up and down the country but also to potential sites of protest, like galleries, so that known militants could be refused access. The women in the pictures below include Mary Richardson (no. 11) who slashed the Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery in 1914 in protest at the treatment of Emmeline Pankhurst in prison, and Kitty Marion (no. 13) a music hall performer and member of the Actresses' Franchise League. It's curious that Marion's publicity photograph has been used here - there are other pictures of her taken by press and police photographers that could have been used but perhaps this full face image was thought more valuable. The picture of suffragette Evelyn Manesta below was taken, apparently under duress, whilst she was in prison. There are other surveillance pictures of Manesta, including one taken by a photographer hidden in a van of her walking around Manchester Prison yard that provides a profile of her body and face. Perhaps this was requested after in order to get a better view of her features - and she seems to be trying to make that as hard as possible by closing her eyes and tensing her mouth. Manesta had been arrested with two other women, Annie Briggs and Lilian Forrester, on 3rd April 1913 after taking part in a protest at Manchester Art Gallery in which the glass covering thirteen pictures was broken. All three remained in custody for a few weeks before being finally tried on 22rd April. Annie Briggs was found not guilty and released, but both Forrester and Manesta were sentenced to serve time in prison. You can read about it here - in Votes for Women from 25th April 1913, on page 433. The surveillance picture of Evelyn Manesta released by the police below appears to show how police doctored the original image for release, removing the arm of the person holding her head in position and replacing it with an extension of her scarf. You can see how the doctored picture was used here (link to National Portrait Gallery website) It's a fascinating glimpse into the lives of suffrage campaigners - and how the authorities treated and presented their images in public space. A quick google of the history of photo manipulation provides some really interesting examples of politicians, press and governments from the late 19th century onwards making changes to photographs to omit unwanted details or people. There are many examples given by campaigners in interviews and their own writing of their interactions with police informants and detectives. In the Suffragette film, the lead character is asked to spy for the police within her local militant group. While it's hard to track down information online about the use of female police informants in this period, there are anecdotal accounts of their presence. Suffragette Mary Richardson, pictured above as no. 11, recorded in her autobiography Laugh a Defiance (1953) that whilst she was in hiding from the police a female visitor came to see her. The visitor gained access because she knew and used the pseudonym or alias Richardson had within the militant campaign. They chatted, and the woman tried to entice her out into the open later that day out to speak to a potential convert to the cause. Richardson's friend was suspicious about her charming visitor - suspicions that were apparently confirmed by the presence of undercover police outside. I presume the records of the women involved in undercover police work during the suffrage agitation do exist somewhere. It's interesting to speculate about their experiences within the movement - were they recruited in the manner the film suggests? Did any of them commit militant acts themselves? How was their information used? How were they embedded within the movement and what happened to them after 1914? Officially, there were no women in the police service before WW1. Both the women who started the Women Police Service (WPS) in 1915 had links to the WSPU, and women were not formally admitted to the Metropolitan Police in London until 1919. Perhaps former female informants worked with former suffragettes in the years after WW1. Consideration of the networks of surveillance and of the example of Evelyn Manesta's doctored image opens up yet another facet of the story of the suffrage campaign, one that has yet to be told in full. It's good to see an acknowledgement of it in the film. Read more about this picture Read more about a 2003 exhibition of the police surveillance pictures of suffrage campaigners

1 Comment

|

NaomiThoughts, reflections, bits of research Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed