|

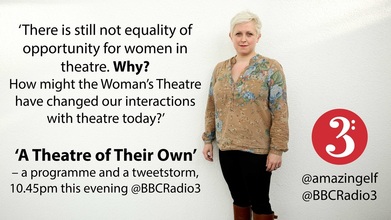

This is the transcript of my talk for BBC Radio 3's Free Thinking Festival, recorded on the 2nd November 2014 at the Sage, Gateshead. It was broadcast on 24th November 2014. The broadcast version was cut, so the transcript below is the" full piece. You can hear the broadcast version by clicking on the picture above - or clicking here A Theatre of Their Own by Naomi Paxton The First Actress, a play produced in 1911 by Ellen Terry’s daughter Edith Craig, one of the most prolific theatre-makers of her day, tells the story of the first woman on the British stage. Set in 1661 in a dressing room at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, we see Margaret Hughes immediately after making her stage debut, racked with anxiety and excitement. In the play, the arguments against the appearance of women on stage are detailed at length, and each time countered by Hughes. However, having experienced a mixed reaction from the audience, and worried she has ruined the prospects for women in theatre forever, Margaret Hughes falls asleep, exhausted. Eleven famous actresses of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries appear to her in a dream to thank and encourage her – among them Nell Gwyn, Sarah Siddons and Madame Vestris. The last to appear is named only “The Actress of To-Day,” played in the original production by actress-manager Lena Ashwell. The Actress of To-Day approaches the sleeping figure of Hughes and says: "When I am born… people will have quite forgotten that the stage was ever barred to us… They will be incredulous that the pioneer actress was bitterly resented – Yet they will be as busy as ever deciding what vocations are suitable to our sex." The play is interesting for a number of reasons – and one of those is that it looks the history of sexism in the theatre full in the face, unpicking the arguments against women on stage and exposing them as not only ridiculous and blinkered, but damaging to the art form they most wish to protect. Nearly all the original cast of the play were members of the Actresses' Franchise League, a group formed in 1908 to support the cause of Votes for Women through their work. They included many of the most successful and respected performers of their day, women and men who openly campaigned for women’s suffrage, and believed that theatre could make a difference in the attitudes of society and contribute to political change. Plays overtly written to support the cause, known as suffrage plays, take time to detail the arguments against giving women the vote and, as in The First Actress, show them for what they are. Both men and women wrote suffrage plays – but women especially seized the opportunity – and the Actresses' Franchise League produced over 120 suffrage plays between 1908 and 1913. The plays are a fascinating glimpse into the campaign - outright propaganda pieces, written with passion, to provoke thought and inspire action. They weren’t only about a different kind of politics, but about a different kind of theatre. Actresses and actors who trained and built their careers together in the 1880’s and 1890’s experienced, through suffrage plays and the theatrical propaganda of the suffrage movement, a new world of performance, one which questioned ideas of participation and spectatorship through what we would now call immersive theatre, street theatre, installations, role play and flash mobs. These performances played with and manipulated images, text, form, space and style – finding novel ways to interact with their audiences and blurring the boundaries between acting and being. I’m often asked where suffrage plays were performed. When people ask this question what they’re really saying is - were these plays ‘properly done’ in ‘proper’ theatres? The answer is yes, they were, but to judge them by that yardstick is, I believe, to fundamentally misunderstand the role of theatre in the political campaign for Votes for Women. The plays were performed everywhere – town halls, drawing rooms, small studio theatres, pop-up theatres, restaurants and skating rinks (both roller and ice). They were at the heart of the movement and full of life and spontaneity, able to quickly respond to changing political situations and to tell stories that reflected the lives of women not often given a voice on stage. They also gave opportunities for women to be involved in production, marketing, finance and administration and to create and maintain networks of their own, within a wider movement that encouraged and championed their involvement and ideas. Lena Ashwell, who played the Actress of To-Day, was in 1911 one of the few women managers working in mainstream theatre. She ran the Kingsway Theatre, near Holborn in London. Women like Ashwell were at a disadvantage financially compared to their male contemporaries, excluded as they were from the theatrical clubs and institutions in which established and aspiring male managers could network, raise finance and seek advice and support. One of Ashwell’s fellow Actresses' Franchise League members, Inez Bensusan, who ran the League’s play department, wanted to change all that for the sake of future generations. In 1913, she announced her idea for a Woman’s Theatre. She wanted it to be: "Run entirely by women… The whole business management and control will be in the hands of women… there will be women business and stage-managers, producers, and so on." The official aims of The Woman’s Theatre were: "To present plays, written either by men or women, which show the woman’s point of view. To provide a new outlet for the activities of women members of the theatrical profession. To run the theatre on a co-operative basis, guarantors sharing in the profits. And to help and forward the Women’s Movement…" Projects to develop Women’s Theatres were springing up in Europe and America at around the same time as in the UK, inspired by the campaign for women’s rights. A Woman’s Theatre in Copenhagen had started in 1896, opening with a play by Magdalene Thorenson, Ibsen’s mother-in-law, a poet, playwright and novelist, whilst 1897 saw the inaugural season of the Theatre Feministe in Paris. Mrs Payton’s Playhouse in Brooklyn, New York opened in 1902 and ten years later, Elizabeth Marbury, who had been Oscar Wilde’s American literary agent, made public her plans for a Woman’s Theatre, also in New York, to be backed by Anne Morgan, daughter of financier J P Morgan. 1913 saw dramatist Frank Wedekind as part of a society in Munich to produce plays by women playwrights – and the foundation of the Woman’s National Theatre in America, initiated by actress Mary Shaw, who also wrote and produced suffrage plays. It wasn’t all about plays – remarkably similar ideas emerged across Europe and America about how this new kind of theatre would be different. Many of the projects had in common the desire for a new physical space - a specially designed venue for networking, learning and socializing as well as theatre-going. Manager Gertrude Andrews had an in-house nursery in her Brooklyn theatre to encourage mothers to attend. She said that it was: “well-equipped…with cribs and maid, so that mothers can bring their babies to the matinee and be free to enjoy it… it enables them, too, to come with their husbands, when otherwise they would be compelled to stay at home.” Mary Moncure Parker’s project of 1912 was for a theatre in Chicago that would cater to a female audience by having daily matinees and providing “tea and social rooms.” Mary Shaw and her collaborators intended that their Woman’s National Theatre building, which they hoped would be in “all the cities of the United States,” would give free performances for children, and have a roof garden in which to show moving pictures. Similarly the woman’s theatre in Copenhagen was intended to be part of a larger, purpose built space, containing “lecture rooms, a restaurant, baths, gymnasium and reading-room.” In London, there were no plans made initially by the Actresses' Franchise League for a new building to house their Woman’s Theatre. They used many different venues for public performances and meetings, and their offices just off the Strand as flexible working space to plan projects, rehearse and teach. However with suffrage shops, women’s clubs and support from many prominent businesses, perhaps the communal space of their Woman’s Theatre had the potential, in an abstract sense, to include the whole of the West End - to share intellectual and social as well as physical space. Rather than make small gains in the mainstream theatre, they dreamed of an entirely different industry, the creation of an old girls network that could compete and eventually collaborate with the old boys network on equal terms. So did the Actresses' Franchise League’s Woman’s Theatre come to fruition? It did. In December 1913, the first season was held at the Coronet Theatre in Notting Hill. Two plays by well respected male dramatists were chosen for the inaugural season – actively deflecting private and public accusations that the Woman’s Theatre would be anti-male, and instead showing it to be part of a European theatre movement that was embracing new forms and ideas. The themes in both plays - Eugene Brieux’s A Gauntlet and Woman on Her Own by Bjornsteirn Bjornson - included many issues that concerned suffragists – double standards, sexual harassment and unequal pay. Suffragist playwright Cicely Hamilton was keen to stress that there was no intellectual elitism at work in this first season, dryly stating that as a commercial venture, the Woman’s Theatre could not afford to only attract "a thinking public." Apart from the fact that the entire venture was being run by women, there was nothing to frighten the average theatre goer. The season was a success, reviews were good and all the shareholders received a 57% return on their investment. Inez Bensusan and the Actresses' Franchise League were delighted – and immediately made plans for another season in December 1914. But this second season was postponed when war was declared. Ever resourceful, an offshoot sprang up - the Women’s Theatre Camps Entertainments - and although the Woman’s Theatre season would be further delayed, it adapted and diversified, producing large and successful War Relief Matinees to raise funds for charities. True to the aims of the Woman’s Theatre, women ran these events, and contemporary newspaper reports show that these new workers were making their mark. Lena Ashwell's decision to employ a female team at her Kingsway Theatre in 1915 was seen not only as pragmatic, given the shortage of men available due to the war, but as a feminist action. The Times announced that: "There will be a woman stage manager, a woman assistant stage manager, and a woman property 'man'…women scene-shifters and an orchestra composed of women,’ describing it as ‘an interesting development of the woman’s theatre movement." Actor manager Johnston Forbes-Robertson, a passionate suffragist, employed a female business manager and stage manager for a special season at the Playhouse Theatre in 1917 – an action the Evening Standard deemed as a "novel and remarkable feature." By the time the war came to an end, much had changed. Theatre ownership and management structures, particularly in the commercial West End houses, were very different. The other projects started by the Actresses' Franchise League during the war – including the Women’s Emergency Corps and the British Women’s Hospital Fund - had broadened their work into many different areas. The Woman’s Theatre didn’t have another season – but League members like Sybil Thorndike, Nancy Price, Auriol Lee and Gertrude Jennings were key players in the new generation of feminist actresses, producers and playwrights working in the commercial theatre after the war. The Actresses' Franchise League remained active, campaigning for equality for women in all areas of social and political life between the wars, through the Second World War and after, before they were wound up fifty years after their foundation, in 1958. Today, a century on from that first season, it is interesting that gender inequalities remain in almost every part of the management structure of the commercial arts field. Since first going to London to study drama in 1997 I have worked in over thirty West End theatres on at least forty different shows in both in the commercial and subsidized sectors, and toured nationally. I haven’t experienced a conspiracy of discrimination, but rather an unthinking maintenance of the status quo that dominates what plays go on, who produces them and who is in them. Do we still need positive discrimination for women in theatre? How, otherwise, will things change? The ‘old guard’ keep dying out but the issues remain - and things aren’t going to change if we don’t or can’t look the hierarchies, histories and structures in the face to see them for what they are. Surely that is preferable to plodding along with our fingers crossed, celebrating individual victories but ignoring the wider problems, which are, as in 1913, about equal representation in the institutions that dominate our political and economic lives. This summer, I played ‘The Actress of To-Day’ in The First Actress, in a performance at a theatre built by Edith Craig at Ellen Terry’s house in Kent. I found the optimism of the piece incredibly moving in hindsight – in 1911, it seemed ridiculous that there had been such discrimination in the history of theatre and inevitable that positive work the Actresses' Franchise League were doing would make sure future generations wouldn’t be held back because of something as arbitrary as their gender. How might a Woman’s Theatre have been different? How might it have changed our interaction with theatres, physically and intellectually, today? It would definitely have more female toilets. It might provide space for discussion that was accessible to all – not just a bar, but a reading room, a library – a place for relaxation and learning, for curious minds both in and out of the profession. Given that women are still overwhelmingly responsible for childcare in our society, it might have a crèche – available to both performers and audiences. Perhaps there would be after school club that introduced children to the theatre as a place in which to engage in storytelling and where they could debate their political ideas. The Woman’s Theatre is one of the most exciting ideas I’ve come across in my research – an ambitious project that aimed to transform the way the theatre industry behaved, change traditions that carelessly excluded women and make theatre that was vital, accessible and representative of its audience. The Woman’s Theatre aimed not to exclude men, but to include women by design. It is still an inspirational idea today. © 2014 Naomi Paxton All Rights Reserved

1 Comment

|

NaomiThoughts, reflections, bits of research Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed